5G

Defending the turf

As consumer telco products become more commoditized, and customers become more attached to their core services, challenging conditions of the past remain in place.

The increased capital-expenditure competition of the past decade will continue, with the investments required in fiber and 4G and 5G increasing over time and putting further pressure on leverage levels. Intensifying competition among operators, will continue to limit their ability to adjust pricing to maintain margins for which returns on equity have already dropped on average below the cost of capital. Furthermore, competition from non-traditional operators, especially media and tech players for over-the-top (OTT) services such as video streaming and cloud storage, will continue to erode revenues. These challenges would only escalate now.

Post consolidation, as we move into the next phase, the question each operator must address is what requires to be done to survive and thrive through the next downturn? India has three private players, each with a share in the vicinity of 30 percent, and BSNL-MTNL have the balance 7-10 percent.

Moving forward, Jio has declared that it is moving to a 500 million customer mark, translating to a 45 percent revenue share.

Bharti Airtel is hell-bent on crossing from 31.4 percent to 35 percent domestic revenue market share, whatever it takes, be it raising USD 750 million to USD 1 billion through the sales of overseas bonds to refinance debt, or raising another USD 3.2 billion by reducing its stake to 13 percent from 37 percent in the entity being formed by the merger of Indus Towers and Bharti Infratel.

Vodafone-Idea, under its new CEO Ravinder Takkar is accelerating the integration process (it has covered districts which constitute 50 percent of their revenues), which will garner substantial cost savings once it is completed by June 2020. The company seems to be in no mood to make way for competition, the two shareholders are committed to putting in more money. VIL has the highest 4G spectrum share amongst telcos, with spectrum re-farming it can up speeds by 50 to 70 percent while competitors have to buy additional spectrum to carry 4G services. And also has monetisation opportunities. The value of its stake in Indus Towers should bring in around Rs 56 billion and it has the option of monetising its fibre business.

BSNL and MTNL are trying every rule in the book to ensure they remain alive and kicking!

The stage is set, the battle getting bloodier, it is the resilient operator who shall significantly outperform the rest of the industry as well as the market overall.

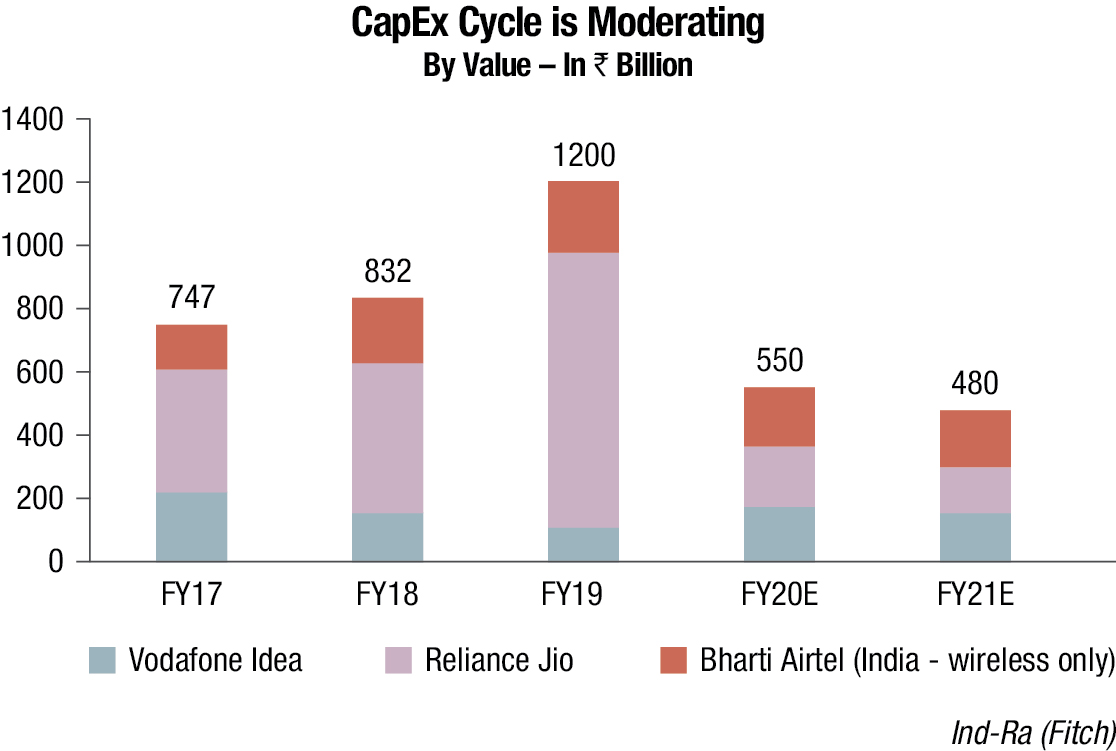

The CapEx intensity, hereon, is expected to witness moderation till the time there is a technology upgrade to 5G, as per an ICRA note. The average CapEx intensity for Indian telcos has been amongst the highest over the 2017–2019 period. Over the last 5 years, the telcos were focusing on expanding their 4G networks and the total CapEx by the top telcos, including spectrum purchases, was around `5 lakh crore. The CapEx intensity for Indian telcos over the last 3-year period has been in excess of 50 percent, as against the world average of 17–19 percent. High CapEx intensity is attributable to sizeable CapEx as well as pressure on sales amid competition.

During FY19, the Indian telcos incurred a CapEx of more than `1 lakh crore. Now with 4G CapEx summiting and 5G still some time away, the CapEx levels are expected to witness temperance to around `65,000 crore for FY20, which, coupled with steady improvement in sales post the uptick in ARPU levels, would result in decline in CapEx intensity to around 30–35 percent, although it will still remain higher than the international peers.

But where will this money come from? Reeling under a debt of more than `7.5 lakh crore, the CSPs are struggling to get funds from multinational banks, overseas investors, and wealth-management companies. Local banks are going through the non-performing assets (resolution) process, while other companies are having difficulty in servicing their debts. So, banks are not seeing any positive aspect in this sector.

Bharti Airtel and Vodafone-Idea are funding most of the CapEx through equity offerings. Both carriers recently raised `25,000 crore each through their respective rights issues, and are also raising funds by selling stakes in units. Reliance Jio also plans to monetize its fiber assets to raise funds, having given up control of its tower assets to Brookfield recently.

Ongoing issues remain. One major unresolved issue is that of IUC. Typically, a telecom operator pays for connecting calls of its subscribers to the company on whose network a call terminates. Currently, an operator is required to pay 6 paise per minute as mobile call termination charge, called IUC. The historical position taken by CSPs was that in a calling-party-pays regime, interconnect cannot be free and globally too there has always been a cost attached to it. Pitching for it to be brought down to zero, Jio’s contention is that IUC is nothing but a subsidy that new operators pay to incumbents; else the more efficient operators will end up paying IUC to the less-efficient and costlier operator.

Subsequently, Jio reduced the ring time for outgoing calls from 30 seconds to 20 seconds, which they maintain is the global standard, and later acceded to 25 seconds.

Jio’s stand is that all operators have had the chance to move to an IP framework for several years. IP-based voice calling (like VoLTE, OTT apps like WhatsApp, and the like) has near-zero cost. And, therefore, the benefit of technology must be passed on to the consumer. By not being able to upgrade legacy networks and continuing to exploit customers through 2G/3G call charges and holding them to ransom, incumbent operators continue to charge users Rs 1.50/minute for voice calls. On an IP-based network, the cost of voice is 0.05 paise per minute (as in the case of a WhatsApp call). Where is the need for IUC in such a case? The cost of old circuit switch networks may be higher. But then why do incumbent operators allow free calling on their own network (on-net calls)?

Whereas Airtel (and VIL) maintain that tariff has nothing to do with IUC, which is essentially a clearing system between two operators, for carrying the calls made by one operator on the network of the other operator. So, the key is to pay for the cost of using the other operator’s network. It is determined by taking into account the cost of running a mobile network – rent for towers, the energy cost for running towers, spectrum costs, and other such costs. The current IUC of 6 paise/minute is unable to cover these costs (the cost of 14 paise/minute is a fair expectation), and the result is that most operators lose money while carrying calls from a 4G-only operator that is now the country’s largest. And if the IUC goes to zero, Jio stands to benefit by approximately `3200–3300 crore per annum.

The IUC was originally proposed to be made nil from January 1, 2020. But TRAI is now reviewing the timeline.

Rajan S Mathews

Rajan S Mathews

Director General,

COAI

“Uninterrupted telecom services are as critical as power and fuel supplies for India’s rapidly expanding economy, which is tipped to touch USD 5 trillion in the next few years.

The telecom industry has invested over `10.44 trillion over the years to take mobile services to every Indian at rock-bottom tariffs. The same industry that has emerged as the backbone for several other sectors, including start-ups, is now struggling to stay afloat because of multiple challenges. The combination of high levies, double taxation and rising debt has meant that telecom is now under tremendous financial stress with doubts arising over its viability and sustainability. Even as tariffs have continued to head southwards, the need for regular and sizeable investments for upkeep of the network and telecom infrastructure has meant that debt on the books of telecom operators has risen nearly 10-fold, from a mere `0.8 trillion in FY09 to `7.7 trillion in FY18.

The return on investment of the private sector has also plummeted from a healthy 14 percent to a meagre one to two percent. While falling tariffs are benefiting customers, the industry is struggling to make ends meet. In just over 18 months, listed players’ market capitalization plummeted to `2.03 trillion on July 23, 2019 from `2.59 trillion on December 29, 2017. Ballooning debt has meant that interest payments as a percentage of EBITDA rose to nearly 71 percent in FY19. The financial stress can be gauged from the fact that the Reserve Bank of India and leading financial institutions and credit rating agencies have raised a red flag over the sector’s viability. In February 2019, Morgan Stanley and Moody’s downgraded India’s telecom sector.

Despite such worrying numbers, the sector is one of the largest taxpayers, contributing `10,000 crore every year to the government treasury. Telcos, in addition to building a world-class telecom infrastructure, have also spent around `76,000 crore in spectrum auctions to transition from 2G to 3G and 4G services. The cumulative payout at spectrum auctions is a whopping `3.68 trillion since 2010. The Indian telecom sector pays 29–32 percent in terms of taxes and levies — one of the highest in the world. Chinese companies, on the other hand, pay just 11 percent.

In light of the challenges, the industry is asking for a practical policy roadmap, so that it can become a major contributor to fulfilling the Digital India vision and building a nation that is digitally and economically robust.”

Adjusted gross revenue. The telcos may be in for another major setback soon, as the final verdict of the Supreme Court over the definition of adjusted gross revenue (AGR) is due any day.

AGR is the basis on which DoT calculates levies payable by operators. The matter has been under litigation for 14 years with operators arguing that AGR should comprise revenue from core telecom services, and DoT defining AGR to include dividends, handset sales, rent, and profit from the sale of scrap, apart from revenue from services. For instance, if an operator buys a commercial property and sells it for a premium, according to this definition, DoT needs to be given a share from it.

Telcos currently calculate AGR on the basis of a telecom tribunal judgement in 2015.

The battle started when telcos migrated to a new system offered by the government in 1999, under which operators agreed to share certain percentage of revenue with the government. Both TRAI and TDSAT have supported the telcos on this issue.

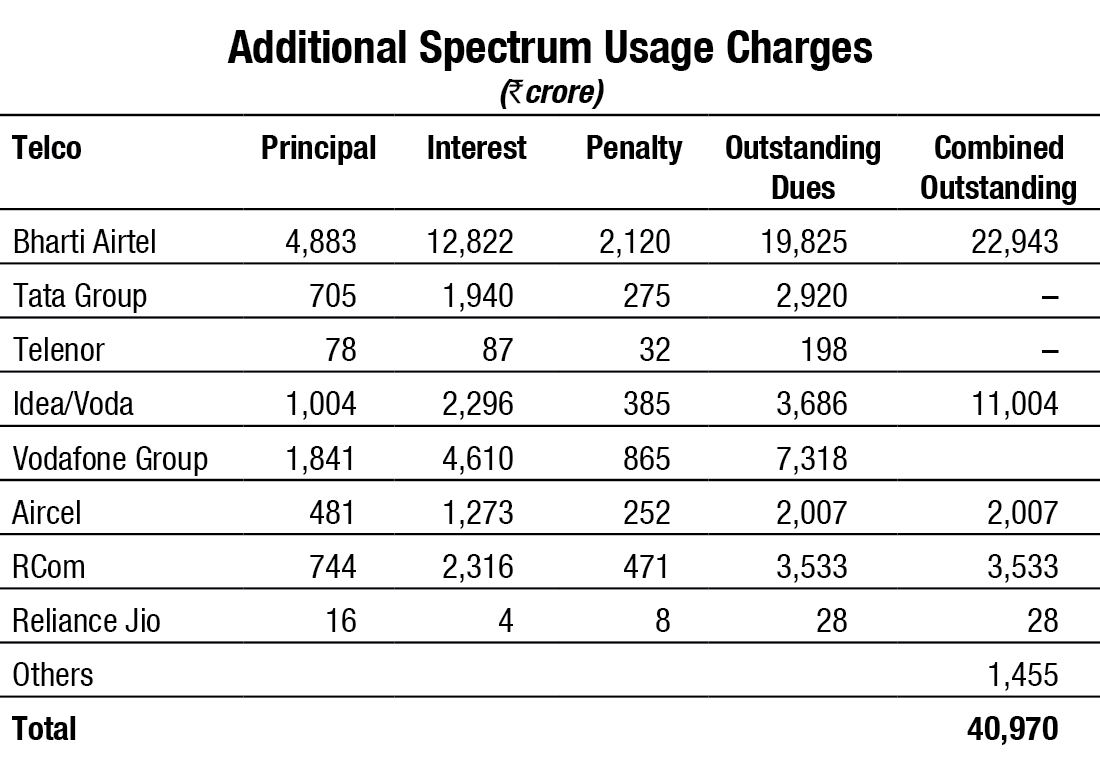

If DoT wins the case, then Bharti Airtel will have to pay `21,682 crore and Vodafone-idea `28,308 crore. For Jio, the amount will be just `13 crore as it entered the sector only three years ago. This amount includes interest, penalty, and interest on penalty ballooning liabilities. That the DoT may find it difficult to recover more than 50 percent of the `92,641 crore from 16 operators, as majority of the companies have either shut down or are on the verge of closure, it is claiming, is another story. The `92,641 crore includes `23,189 crore as the original disputed amount, `41,650 crore of the levy of interest, `10,923 crore as penalty, and `16,878 crore as interest on penalty. Just about three years ago, the total dues were just `29,474 crore.

But this is not all. If it goes in the government’s favor, the telcos will need to pay `40,970 crore as additional spectrum usage charges. This will be over and above the `92,641 crore license fees and penalties.

USO and license fee. As the industry is struggling for funds, the Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI) has appealed to the DoT that the total license fee be brought down to 4 percent. At present, the total license fee is 8 percent of AGR, where 5 percent is for the USO Fund fee, and the license fee is 3 percent.

To achieve the total telecom license fee of 4 percent, COAI has suggested a roadmap of reducing the USO contribution immediately to 3 percent with the ultimate objective of doing away with the levy in the next 2–3 years in line with the recommendations of the telecom regulator, and reducing the current license fee from 3 percent to 1 per cent of AGR.

Of the `99,674 crore collected for the USOF between the fiscals 2003 and 2019, as much as `50,554 crore remained unutilized as on June 2019, and is being diverted to the Consolidated Fund of India. In any case, this amount is more than the requirement to connect 43,000 remaining unconnected villages, according to COAI. TRAI, CAG, and the telecom ministry have also voiced their concerns over this.

Paying one-time spectrum charge (OTSC) for transfer of airwaves, which were acquired administratively and not through an auction. The clause under M&A rules states that in case of judicial intervention on the issue of OTSC, the merged or the acquiring entity must further give a bank guarantee of an amount equivalent to the demand raised by the DoT, till the case is resolved.

The TDSAT had ordered DoT to take the merger of Tata Teleservices’ consumer mobility business with Bharti Airtel on record, after partially staying the government’s order of raising an OTSC demand of `8300 crore on the telco. The tribunal asked Airtel to pay up just `644 crore, after which the merger would be deemed complete. DoT is expected to appeal the TDSAT order in the SC, shortly.

In the Vodafone-Idea merger case, TDSAT last year asked the DoT to return bank guarantee worth `2100 crore toward OTSC to the telco, after the carrier won a case against the government in the tribunal. The DoT then appealed in the Supreme Court, which has asked the telco why it should not submit the bank guarantee since it was a prerequisite in the M&A guidelines. The matter is still being heard.

TRAI has floated a consultation paper on reforms required to be made in the existing guidelines on transfer/merger of licenses to enable simplification and fast tracking of approvals.

5G Auction.

While the service providers are demanding that the auction of 5G spectrum be delayed, the authorities plan to sell licenses at the end of this year.

The telcos, with huge debts, declining average revenue per user, and an abysmal return on capital, are not in a position to make huge investments in the new spectrum, license fees, and infrastructure and equipment.

The reserve prices for spectrum at USD 70 million per MHz in India are the highest in the world as compared to USD 26 million in Italy, USD 18 million in South Korea and USD 10 million in the UK. Previously, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) recommended a base price of `492 crore per unit for spectrum in the 3300–3600 GHz frequency band. Including other bands, 8294 MHz would be up for sale in one of the biggest spectrum auctions in the world. The unsold mobile spectrum has cost India `5.4 lakh crore in economic loss since 2010. Forty percent of spectrum since the 2010 auctions has remained unsold.

Moreover, operators still see little use for the 5G standard in India. Even outside India, where services have been launched, operators are struggling to come up with lucrative use cases for the technology. Judging by previous experience, offering higher-speed connectivity alone is unlikely to pay off.

A USD 30-billion investment will be required. Telecom operators will need to invest `2.1 lakh crore (USD 30 billion) to roll out 5G services in the country, according to an analysis done by UBS.

Airtel and Vodafone-Idea will each need to spend `14,000 crore annually on 5G radio and fiber CapEx spread across 5 years, implying 65 percent and 85 percent of Airtel’s and Vodafone-Idea’s current annual India CapEx run rates, respectively. The CapEx for Jio would, however, be lower, due to its larger tower footprint and higher proportion of towers on fiber backhaul, compared with Bharti Airtel and Vodafone-Idea. The overall estimated CapEx spends can be lowered by 15–20 percent if the three Indian telcos share towers and fiber resources.

The Huawei issue. Huawei has been facing several regulatory roadblocks related to issues of privacy and data theft after reports claimed the company embedded snooping software in the source code of its servers. Huawei has invested about `24,500 crore (USD 3.5 billion) in India and operates a manufacturing unit in Chennai for production of telecom equipment for 2G, 3G, and 4G.

Huawei is open to expansion into 5G equipment production and export, but that move depends on it being allowed to participate in the domestic operations of 5G network as well. Ritchie Peng, chief marketing officer with Huawei, said earlier this month, “European operators have said (in interviews to media) that without Huawei’s 5G technology, the 5G roll-out will be postponed by two to three years. We hold the same expectation for the India market, as we will use our fast 5G technology to meet the needs of Indian operators and consumers because now we shall focus on how we can use our best technology to serve their needs.”

Then there is the Donald Trump angle to Huawei’s story. The Chinese telecom equipment maker is battling intense pressure from the US, which is pushing allies to keep the company out of 5G telecom networks because of the suspicion that the Chinese government used the company for spying. Huawei has tried to dispel fears around Trump’s charges. Pen pointed out, “Around the world, Huawei has already secured more than 50 commercial 5G contracts, which shows that these customers from around the world believe that Huawei’s 5G is secure.”

Meanwhile, Indian companies are attempting to test 5G. Reliance Jio has joined hands with China Mobile, China Telecom, China Unicom, Intel, Radisys, Samsung Electronics, Airspan, Baicells, CertusNet, Mavenir, Lenovo, Ruijie Network, Inspur, Sylincom, WindRiver, ArrayComm, and Chengdu NTS to develop 5G network solutions based on open standards and support interoperability. Airtel is also a member of O-RAN, or open radio access network.

In comparison, 5G is more or less ready to roll out in advanced countries. 2019 is an introductory year at best while 2020 looks to be the year 5G begins to really kick in. 303 deployments by 20 operators in 294 locations have already been made. Further, Ovum predicts that by end of 2021, there will be 156 million 5G connections worldwide and 32 million in North America alone. In India, not a single large live trial has yet been initiated, and the guidelines for the release of experimental or trial spectrum are still work-in-process. We could be as many as three years behind South Korea, Japan, Australia, the US, China, France, and Germany in rolling out 5G networks. We will have to race at double the speed to ensure that the gap does not widen further.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login